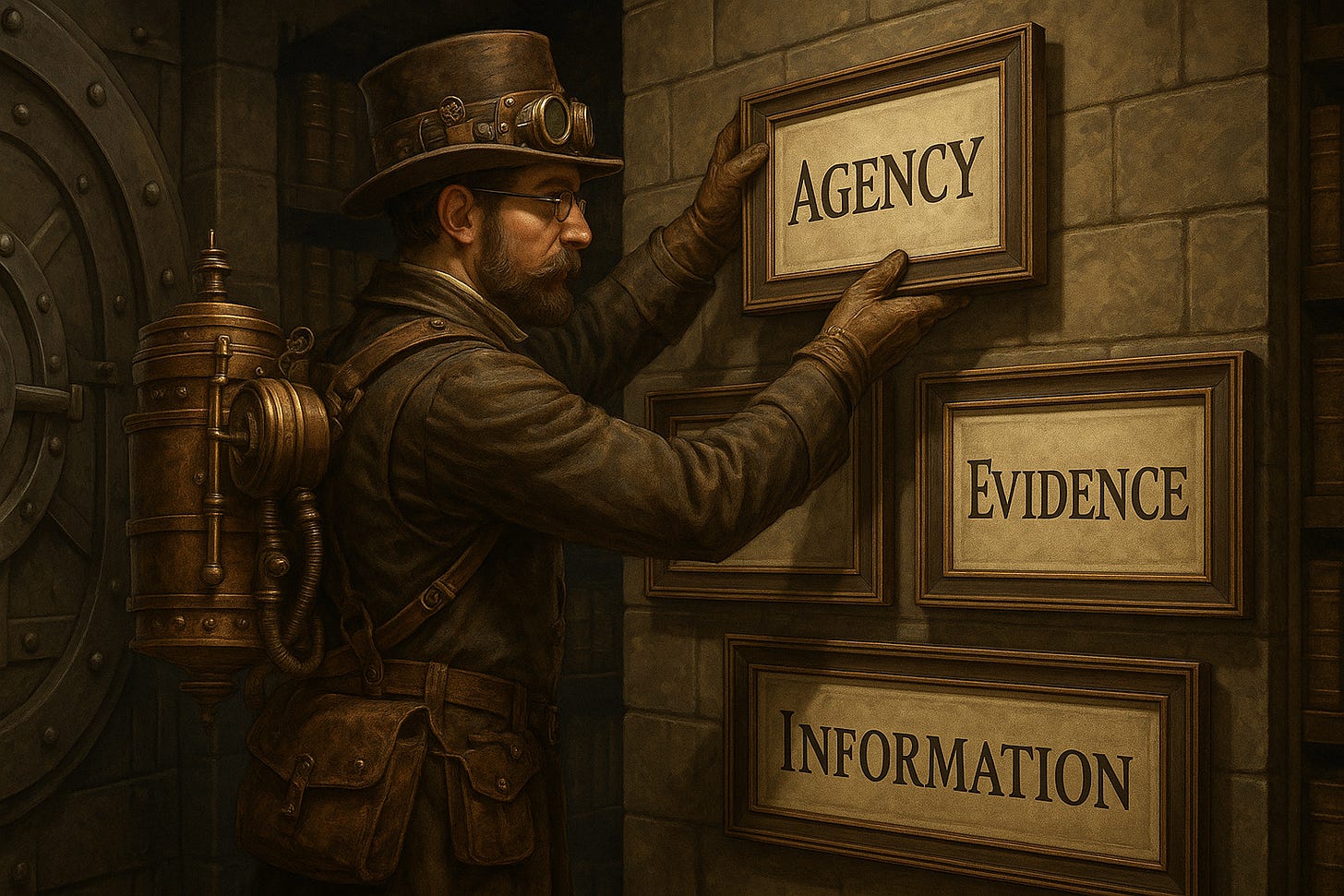

When Records Act

Discovering the Agentic Nature of Records

Every once in a while, a paper finds you at just the right moment. Scrolling through Google Scholar this week, I came across Geoffrey Yeo’s recent article, “Archives, records, and information: Terms, concepts, and relationships across linguistic cultures” (Boletim do Arquivo da Universidade de Coimbra, 2025). What stopped me in my tracks wasn’t just Yeo’s usual precision in tracing terminology across languages — though that’s here in spades.

I’ve always appreciated Yeo’s contributions, he has a gift for clarifying our most contested terms and situating them historically, linguistically, and philosophically. His books on records and data have been touchstones for many of us. But in this paper, one idea leapt out at me in a way I hadn’t encountered before: records are not just carriers of information; they are agents that act in the world.

This wasn’t entirely new. I’ve heard echoes of it in debates about performativity, speech act theory, and the role of records in constituting social realities. But here, Yeo frames it with a clarity that made me stop and reread: records don’t just document an action, they perform it.

When a Record Does Something

Think of an email with the words: “I resign.” That email isn’t merely reporting a fact. It is the resignation. Similarly, a signed contract doesn’t just memorialize an agreement; it brings the agreement into existence. A marriage certificate doesn’t only describe a ceremony. It confers legal status.

These aren’t just static inscriptions. They’re instruments. They change relationships, transfer rights, create obligations, and redefine identities. In other words: records do things.

Persistence Across Time

Another layer of their agency lies in persistence. Information can pass quickly — fleeting data points or facts absorbed and forgotten. But records endure. A will continues to bind heirs long after the author has died. A treaty continues to stabilize relations between nations decades, even centuries, after the ink has dried.

Because they persist, records don’t just enact change in the moment; they sustain it. They preserve promises, enforce obligations, and extend the performative power of actions across generations.

Why This Struck Me

I’ve often described records as evidence, as memory, as information. Those frames are useful, even essential. But Yeo’s framing unsettled my shorthand. Evidence is retrospective; memory is reflective; information is descriptive. Agency, by contrast, is active.

Seeing records through this lens reframes our role as professionals. We are not simply preserving traces of the past or curating information flows. We are stewards of instruments that make and sustain reality.

Why It Matters Now

In a professional climate where “information governance” and “data management” dominate the conversation, it is tempting to collapse records into information. And yes, information has allure, it feels modern, digital, strategic. But if we let records be subsumed by information, we risk losing sight of what makes them distinct.

Information can describe, persuade, or inform. But records can bind, compel, and authorize. They anchor accountability in ways information alone cannot. They act as bulwarks against forgetting, denial, or revision.

If we ignore the agentic nature of records, we leave open the possibility that organizations, or societies, will treat recordkeeping as just another IT function, when in fact it underpins rights, responsibilities, and trust.

Seeing Records Anew

What I appreciated about Yeo’s framing is that it wasn’t abstract for abstraction’s sake. He ties the argument to practical examples: apologies in email, Inka khipus, digital signatures, treaties, contracts. These are reminders that the “agentic record” is not a theoretical curiosity; it’s at the heart of daily life and global governance alike.

For me, this insight reframes the stakes of records work. It underscores why our professional voice matters, not just in managing “information assets,” but in protecting the integrity of the instruments that constitute our social, legal, and cultural worlds.

Closing Thought

I’ve read Yeo before, but this framing made me pause. It clarified something I had perhaps known implicitly but never seen expressed so sharply: records are not passive artifacts. They are actors in their own right.

That insight has consequences. It changes how we think about preservation, access, accountability, and professional identity. And it reminds us why, even in an age saturated with data and information, records still matter, not only for what they say, but for what they do.