Life Cycle vs. Continuum Models in the Age of Digital Sustainability and Digital Sobriety

A MetaArchivist White Paper

Introduction: Digital Sustainability and Digital Sobriety

Digital technologies have enabled organizations to create, store and share information at unprecedented scales, but they also bring environmental consequences. A 2024 white‑paper by OASIS Group notes that the generation, storage and management of digital data require substantial energy and that the “store it all” mentality contributes to carbon emissions (oasisgroup.com). Digital sustainability refers to responsibly using digital technologies to minimize environmental impact and promote long‑term viability—examples include energy‑efficient hardware, green data centers, waste reduction and sustainable software development (purplegriffon.com). Digital sobriety goes a step further; it advocates reducing consumption of digital resources to lower our ecological footprint. Symposium participants at Concordia University highlighted that digital files kept in cloud servers have hidden ecological costs and recommended reducing the volume of information retained, compressing data and ensuring there is a clear use case for archived materials (concordia.ca). Digital sobriety in corporate settings involves limiting digital tool use, repairing rather than replacing equipment and optimizing energy consumption while promoting employee awareness (blog.idecsi.com).

These sustainability concerns challenge traditional records‑management paradigms. The two dominant models—records life cycle and records continuum—were developed before environmental issues became a priority. Analysing them through a sustainability lens reveals how each model can support or hinder digital sobriety and decarbonization initiatives.

The Records Life‑Cycle Model

Description

The life‑cycle model views records as moving through sequential stages. A guidance document from the New York State Archives divides the cycle into four phases: creation (or receipt of records), active use (when records are frequently referenced), inactive storage (records moved to a records centre when they are no longer needed regularly) and disposition (records either destroyed or transferred to archival storage) (archives.nysed.gov). This model assumes that records’ value changes over time, emphasizing that non‑permanent records should be disposed of to prevent inefficient storage and ensure identification of records with enduring value (archives.nysed.gov). Responsibilities are neatly divided—records managers handle the first three stages, and archivists receive materials at the end of the cycle.

Alignment with Digital Sustainability

The life‑cycle model’s focus on planned disposition and controlled retention periods offers opportunities to reduce the environmental footprint of recordkeeping:

Encouraging disposal: By defining retention schedules and routinely destroying records that have fulfilled their legal and administrative obligations, organizations avoid indefinite accumulation. This supports digital sobriety by limiting unnecessary data volumes (archives.nysed.gov).

Structured audits: Best‑practice guidelines for digital decarbonization recommend a robust digital records lifecycle management strategy that clearly defines stages from creation to archiving, enabling systematic audits and disposal of outdated or irrelevant records (oasisgroup.com). Regular audits help identify redundant, obsolete or trivial (“ROT”) data; eliminating them frees storage capacity and reduces energy use (oasisgroup.com).

Efficient storage solutions: The OASIS white‑paper advocates tiered storage, where frequently accessed records reside on high‑performance media and less critical records are migrated to lower‑cost, energy‑efficient storage (oasisgroup.com). Such practices align with the life‑cycle’s concept of moving inactive records to secondary storage.

Challenges in a Digital Context

Despite these advantages, the life‑cycle model faces several challenges when applied to digital sustainability:

Delayed archival intervention: In paper environments, transferring records to archives after decades was acceptable; digital records, however, may require early preservation actions to maintain authenticity and readability. The PERICLES project noted that transferring digital records after 20–30 years is too late and that paper‑based practices do not translate easily into digital contexts (tate.org.uk). Delayed intervention can lead to format obsolescence and may necessitate energy‑intensive recovery processes.

Rigid separation of duties: The life‑cycle’s division between records managers and archivists can hinder holistic sustainability strategies. When archivists only become involved at the disposition stage, opportunities to influence creation, metadata capture and appraisal decisions—which affect storage demands—are missed.

Information loss vs. environmental costs: Aggressively disposing of digital records might reduce carbon footprints but risk erasing significant evidence or cultural memory. Sustainable practices must balance environmental reduction with accountability and heritage.

Large volumes of dark data: The model’s assumption that records move predictably through stages can be undermined by digital systems that duplicate or replicate data across environments. Without proactive audits, backups and file‑versions can accumulate, leading to “dark data” that consumes storage and energy (oasisgroup.com).

The Records Continuum Model

Description

Developed in the 1990s by Frank Upward, the records continuum model reconceptualizes recordkeeping as a multidimensional process rather than a sequential life cycle. It posits four interrelated dimensions—Create, Capture, Organize and Pluralize—that occur simultaneously across space and time (en.wikipedia.org). The model emphasizes that records can be both current and archival at the moment of creation, integrating evidential, transactional, identity and recordkeeping axes (en.wikipedia.org). This framework dissolves strict boundaries between records management and archival functions; collaboration begins at record creation, with metadata capture, classification and context recorded early (margotnote.com). Archivists and records managers work together to determine enduring value, and decisions about disposal or pluralisation (wide dissemination) happen continuously (margotnote.com).

Alignment with Digital Sustainability

The continuum model offers several sustainability advantages:

Early appraisal and metadata capture: By involving archivists at creation, the model supports thorough appraisal and rich metadata that can improve future retrieval and reduce unnecessary storage. Accurate metadata tagging allows organizations to identify valuable data and efficiently archive or delete outdated information, a key recommendation of digital decarbonization frameworks (oasisgroup.com).

Integrated governance: The continuum’s holistic view aligns with sustainable information governance practices. Policies can address data minimization, metadata standards and classification across the entire recordkeeping environment, ensuring that only necessary data are collected and retained (oasisgroup.com).

Adaptive preservation: Because digital objects may continue to evolve, the continuum model accommodates ongoing management, migration and pluralization. This flexible approach can help reduce resource waste by avoiding unnecessary duplication or late, energy‑intensive interventions.

Sustainability Challenges

While the continuum model addresses many digital complexities, it also raises sustainability concerns:

Increased storage and energy use: The continuum emphasizes pluralization and broad accessibility. Creating multiple copies, maintaining persistent access and capturing rich context can significantly increase storage requirements. A study of Swedish and Danish public archives noted that early transfer of born‑digital records (after five years) led to rising maintenance costs, including storage, monitoring and migrations, which drained resources (researchgate.net). Such demands may conflict with digital sobriety’s goal of reducing energy consumption.

Blurred responsibilities: When records management and archival functions are integrated, accountability for disposal decisions can become ambiguous. Without clear procedures for eliminating redundant records, organisations risk retaining more data than needed.

Complexity and resource intensity: Implementing a continuum approach requires sophisticated systems, continuous metadata management and ongoing collaboration. Smaller organizations may lack the capacity to support such infrastructure without disproportionate energy and financial costs.

Digital Sobriety and Decarbonization: Bridging the Models

The emerging movements of digital sobriety and digital decarbonization challenge both models to rethink assumptions. Key insights include:

Hidden environmental cost of digital storage: Concordia University’s symposium warned that digital files stored in cloud servers have hidden ecological costs and recommended upstream reduction and compression (concordia.ca). OASIS Group similarly noted that digital data were long considered carbon‑neutral but that inefficient storage practices significantly contribute to greenhouse‑gas emissions (oasisgroup.com).

Records management as a tool for decarbonisation: Digital records lifecycle management, regular audits and disposal of unnecessary records are critical for reducing data clutter and energy use (oasisgroup.com). Records management plays a vital role in minimizing digital waste, aligning the life‑cycle model with digital decarbonization.

Data classification and metadata: Digital decarbonization frameworks emphasize classifying data (core business data, third‑party data, transient external data and backup/archive data) and reviewing backups to eliminate unnecessary retention (oasisgroup.com). Metadata tagging and heat‑map analyses help identify data that are rarely used so they can be deleted or moved to lower‑impact storage (oasisgroup.com).

Digital sobriety practices: Corporate digital sobriety initiatives urge limiting digital tool usage, repairing rather than replacing devices, optimizing energy consumption and educating users (blog.idecsi.com). They highlight reducing data volume, optimizing storage and raising user awareness as key issues (blog.idecsi.com). Records managers can support these aims by encouraging employees to avoid creating duplicate files, use version control and delete obsolete documents (blog.idecsi.com).

Spring cleaning campaigns: The University of California’s 2025 digital spring clean‑up challenge encourages staff to spend a few minutes each day deleting unnecessary documents and sorting emails. It explicitly notes that data storage has an environmental cost, so reducing digital footprints supports sustainability (link.ucop.edu).

Need for sufficiency, not just efficiency: Scholars argue that focusing solely on technological efficiency only reduces unsustainability; true sustainability requires sufficiency—absolute reductions in the amount of digital content preserved (mdpi.com). This demand challenges both models to reconsider the quantity of information retained.

Comparative Analysis and Recommendations

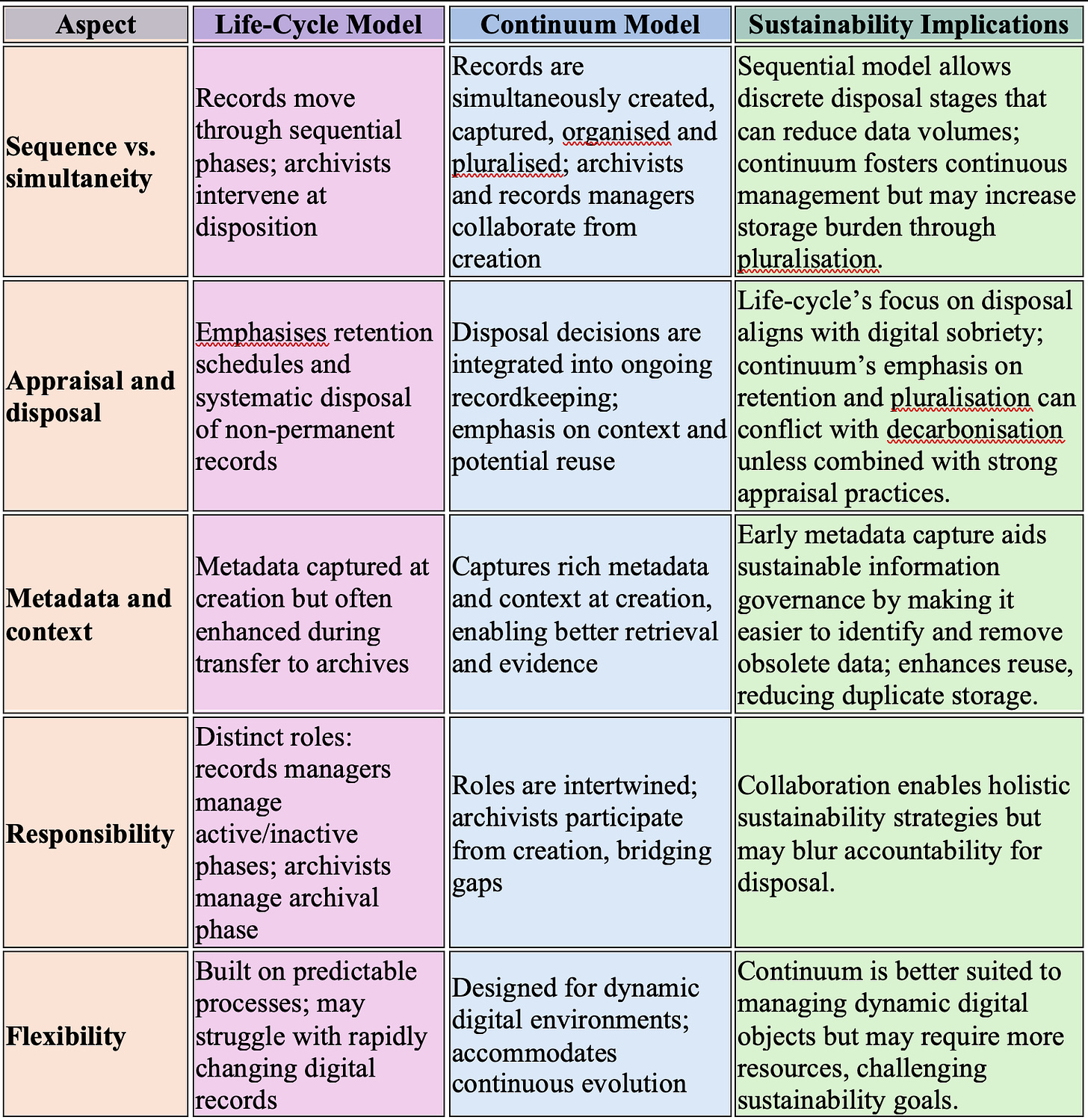

Comparing Life‑Cycle and Continuum Models

Recommendations for Sustainable Records Management

Integrate sustainability into policy: Organizations should embed environmental principles into records management policies. Policies should include data minimization, disposal guidelines, and energy‑efficient storage requirements (oasisgroup.com).

Adopt a hybrid model: Use the life‑cycle model’s structured appraisal and disposal to control data growth, while borrowing from the continuum model’s early appraisal and metadata practices to capture context and enable informed decisions. Early involvement of archivists can ensure that only valuable records are preserved while unnecessary data are disposed of sooner, reducing energy use.

Implement regular audits and spring‑cleaning campaigns: Encourage departments and individuals to review their digital holdings routinely, delete obsolete files and align with retention schedules. Institutional campaigns like UC’s digital spring clean‑up raise awareness that data storage has an environmental cost (link.ucop.edu).

Enhance metadata and classification: Tag new digital records with rich metadata to facilitate automated identification of value and obsolescence (oasisgroup.com). Conduct heat‑map analyses to identify underused data and focus preservation resources on valuable information (oasisgroup.com).

Use tiered and green storage solutions: Store frequently accessed records on high‑performance media and migrate rarely used records to low‑energy storage. Leverage cloud services with green certifications to ensure infrastructure is powered by renewable energy (oasisgroup.com).

Educate and engage users: Promote digital sobriety by educating staff about the ecological impact of digital technologies and encouraging practices such as limiting attachments, co‑editing documents instead of exchanging copies, and avoiding duplicate files (blog.idecsi.com).

Apply sufficiency principles: Beyond efficiency, adopt sufficiency strategies that question whether preserving a record is truly necessary. This may involve re‑evaluating long‑standing assumptions about the need for perpetual digital preservation and embracing selective retention to align with planetary boundaries (mdpi.com).

Conclusion

The life‑cycle and continuum models offer valuable frameworks for managing records, yet neither alone fully addresses the environmental challenges posed by the digital age. The life‑cycle model’s emphasis on disposal and retention schedules aligns with digital sobriety, but its late archival intervention can leave digital records vulnerable to obsolescence. The continuum model better reflects digital realities and encourages rich metadata capture but risks increased storage and energy consumption. By integrating sustainable practices—data minimization, metadata enrichment, tiered storage and user education—records professionals can adapt both models to support digital sustainability and sobriety goals. Ultimately, a hybrid approach that harnesses the strengths of each model while prioritizing environmental responsibility offers the most promising path forward.